Last week saw the end of the 2023 New Zealand National League and the end of the season’s activities. The result was 5th place out of 10 teams. It was a frustrating result as we could have finished in third place if we had won our last game. However, while the teams around us were able to recruit players with money, I think that we did fairly well for a volunteer club where everyone plays for no pay.

The year 2023 was a year of eastbound travel for me: in January, I went to Spain to try out for football, which I had always wanted to do, and played for just under two months, but was unable to get a contract. From March to July I had to stay in Japan for less than five months in order to obtain a visa to go to New Zealand. When could I apply for a visa and when would it be issued? I worked at various jobs to recover my savings, which I had used up on my trip to Europe, while constantly dealing with stress. Finally, I was able to return to New Zealand in mid-July.

But then again, I don’t know where I will be staying, I can’t work because of my visa, and I am constantly living with stress.Anyway, I’m living in a bizarre life where I can’t even plan a month ahead. That’s the situation.

In the 2023 season, I played football in three countries.

Two months in Spain, four months in Japan and four months in New Zealand.

I only got to play official matches in New Zealand, but even so, I played in each country and felt the differences in each country.

For me, the differences are the most interesting and exciting part of football.

So this time I would like to write about the differences I felt playing in each of the three countries from an on-the-pitch perspective.

Spain

In Spain, I trained with a team in the fifth division (although I didn’t sign a contract). Then later I played for a team in the sixth division, which is the second team. To be honest, I felt there was a considerable difference in level between the fifth and sixth divisions.

It’s a bit presumptuous to talk about Spanish football after only playing for three weeks each, but I still feel that I absorbed a lot.

There was definitely something there that formed the Spanish football that I have long admired.

Tiki Taka.

When I think of Spain, I think of Tiki Taka. Having grown up watching Barça games, I have a longing for Tiki Taka.

Of course it depends on the characteristics of the team, but the team I was part of was a team that valued ball retention, so Tiki Taka was there. We would always do rondos in training and I had the impression that they were very important and enjoyed working on it.

The first surprise was that no one was bad at it. In Japan and New Zealand, there were always players in the team who were not good at passing, but in Spain, even the defence players did not seem to be bad at it at all. In other words, the image shared by everyone was very high.

What shocked me personally was the quality of the direct passing. Having played in Japan and New Zealand, my sense was that the theory was to trap a strong pass or drop it to a nearby player. The point is that once you try to slow the ball down because a strong and fast pass increases the chance of making a mistake.

However, in Spain, the player who received a strong pass would connect with another strong pass inside kick with the same momentum. Defences often lost their aim after two fast passes.

I was surprised at the skill of the player who could direct a strong, fast pass, but also at the speed of decision-making to be ready for that option.

Speed and intensity of changeover.

I said Spain is Tiki Taka, but the biggest surprise I experienced playing in Spain was the high intensity.

First of all, the moment you lose the ball, the switch to defence is extremely fast.

The spirit and intensity of the chase backwards against the ball carrier was especially tremendous. I thought that perhaps they have been drilled into them the principle that it is not good to be defending backwards.

And the intensity to get the ball. In Japan, you are taught to slowly close the gap between you and the ball carrier without jumping in, but in Spain it was different. They all jumped in and came for the ball with a foot-hunting vigour. If they tried to overtake you, they would pull on your uniform and stop you, even if it meant fouling you.

If I had to imagine it, the standard attitude for winning the ball seemed to be that of a player like Wataru Endo.

Surprisingly, the biggest impact I had in Spain was not in the passing game, but in the defensive intensity.

I was convinced that without this defensive intensity, Tiki Taka, the very essence of Spanish football, would not have been born.

Development age group playing the same football as adults.

I had the opportunity to play a practice match with Granada’s U17s and I played too.

Although they were under 17, the better players were already playing in the higher categories, so it seemed that many of them were actually 15 years old. However, they were playing on equal terms with us adults, who are slender in body.

Above all, their positioning in the build-up and the way they moved the ball were so washed out that it didn’t feel like they were playing against 15-year-old players.

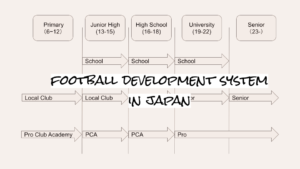

A high school football match in Japan will never look the same as a J-League match. In Japan, primary schools students are taught to play primary schools football, junior high school students to play junior high school football and high school students to play high school football. And when they grow up, they learn to play adult football.

In Spain, however, there seems to be a common image of football from the developmental age to adult football.

This may be the reason why Spain produces players who make their first team debut at the age of 16 or 17 every year.

Outside turns and inside passes by smaller players

Iniesta’s outside turn (and inside too) is an art. In fact, I realised as an adult that if you can make that turn, you lose the ball a lot less often. In Spain, many players used the outside turn very beautifully.

Few players used the tricky techniques taught at primary schools age in Japan, and I got the impression that many players were able to demonstrate their basic skills at a high standard.

Also, many Spanish players are small in stature and have a thin body line. However, they kicked stronger, faster and more compact inside passes than any big Japanese or New Zealand player.

It made me realise that inside kicking is all about the way you use your body and your core.

Also, to put a finer point on it, most of them had a fluid kicking motion, with a quick swing from the hip to the end below the knee, rather than the inside kick where they create a surface on the inside and push it out, which is common among Japanese players.

Japan.

During this stay in Japan, I participated in social, working-class football rather than a high-level environment. The level and intensity was of course lower, but I had the opportunity to play with a variety of players from foreign leagues and it was interesting to see football in a different environment.

On the other hand, I also had to keep myself in good condition, so I took part in training at my alma mater’s university. This is not a high-level environment either, but it was very good to see them working hard.

Still, there are a lot of good players.

Many of the players who take part in social football have already retired from football. But many of them were still good players. They were famous players in high school and university, and their skills are still alive and well even though they have retired.

It was a glimpse of the large number of people playing football in Japan.

Also, in my subjective opinion, I feel that Japan is very strong when it comes to social football. When European players retire, their athletic ability deteriorates and their ball control looks awkward, but Japanese players are very dexterous.

I was surprised to see how good many working people are when I went to individual soccer matches.

Few players are able to grasp the whole picture of the game.

My impression of Japan is that many players have a low football IQ, if I may put it that way. This is easy to understand when you think of players who are technically and physically very good, but are unable to show it in a game.

I feel that there are many players in Japan who only enjoy dribbling past two or three players, or who only enjoy breaking the deadlock.

My personal impression is that there are not many players who see the overall picture of winning the game of football and play within that context.

More specifically, I felt that many players have poor positioning, are not good at simple plays and do not understand defensive theories.

Conversely, I saw a clear difference in players with such a perspective, even in amateur or social-like football.

Why are there so many players in Japan who make poor decisions? We do not know the reason.

Serious.

Practice at the university was still very serious and serious. Laughter is not allowed during practice. I don’t think there is anything wrong with that, and I personally feel more comfortable in that way. I’ve already got used to the practice atmosphere abroad.

But it’s also good to know that practice is conducted in a completely different atmosphere abroad.

Jokes and laughter fly around during practice, and yet the switch is flipped at a moment’s notice. I feel that Japanese football (especially in the development age) should know that this is also one of the right things to do.

You can’t turn it off when the flow is bad. I have experienced this many times playing for Japanese high schools and universities.

On the other hand, overseas players and teams switch quickly. They don’t drag out mistakes and the atmosphere after a loss is not bad. I personally feel that it is not surprisingly not bad to break a bad trend in a different way.

Can’t kick long balls.

I got the same impression when I participated in university training and in social football. It means that not many Japanese players can kick the long ball. I think this can be interpreted as not knowing how to use the long ball very well.

Specifically, long balls from centre-backs and side-backs to opposing players. In New Zealand, Australia and Spain, all the countries I played in, they had players who could kick the ball to the opposite corner, as a matter of course.

And because positioning is based on this long ball, the diagonal players are not squeezed, and a good amount of space can be secured in midfield.

In Japan, however, many players and teams did not have that long ball as an option, and there were many situations where the players were playing in half the pitch. I don’t know why, but I’m sure it’s a muscular problem.

Unchanged training menu

The most interesting thing about playing in Japan for the first time in a long time was that the training regimes I experienced in my developmental years still exist today.

The most typical one is basic training.

It doesn’t mean that basic training is bad. And I don’t think it’s necessary to change the practice menus that have existed for a long time.

However, in New Zealand and Spain, we often saw the same kind of practice menus that the professional teams are working on being adopted immediately. In Japan, I didn’t see that very often.

The quality of practice itself is very low in New Zealand, but when I observed academy practices, the practice menus were well thought out and I often thought that they were good practice menus.

I think the reason for this is language.

If you are able to use English in this day and age of social networking, the amount of information you can acquire increases by an order of magnitude. From New Zealand, we can catch up with information on European football in English, which is located on the other side of the world, as a matter of course.

On the other hand, Japanese people have to overcome one language barrier when acquiring information. It takes time for information on what is happening in cutting-edge football to be translated into Japanese and flow in.

This may be the reason why Japanese people tend to create coaching methods based on their personal experiences, while people from overseas tend to acquire information from other sources.

I would like to write more about this area of language and football at some point.

New Zealand.

I joined the team in the middle of the league, played a few games in the regional leagues and soon after in the National League. I played a total of 16 games and played almost a full match. It was my first official game in a year and my game and playing feel was not so good, but I take it as a positive that I finished without any injuries. I also recorded a mileage of about 13 km in each game, which I feel was not bad. Next season I hope to build on this condition and improve the quality of my play and decision-making.

I think the U20 rule is an essential part of New Zealand football. Various measures are set each year to encourage the active use of U20 players in official matches. This year there was a rule that at least 10% of the total playing time of the team must be given to players under the age of 20 in every game. I personally feel that since the U20 rule was put in place, the level of New Zealand’s top flight has continued to descend.

Overall, many teams play similar football.

There is an impression that all New Zealand teams play similar football.

Most teams connect the ball from their own half and put pressure from the front when defending. The difference in quality and the quality of the players is what decides who wins and who loses.

I personally believe that in New Zealand, where the number of players is still very small, the probability of various types of football being born is not high.

Modern football tends to pursue the optimum solution for winning, but I personally think it would be interesting to see more teams with different characteristics emerge.

There are a surprising number of highly capable players, but…

New Zealand is an amateur league, but there seem to be a surprising number of highly skilled players.

Many foreign players, especially from overseas, are good players.

However, on the other hand, it is not as if they are tactically sophisticated. Maybe the style is not to give them too many tactics as a team, but to let them solve problems individually. I don’t know the details of this, as I think it has something to do with the education of the country.

But anyway, it is clear that the level of football in this country is not very high in terms of tactics. Conversely, the teams with good tactics are quite tough.

The last team we played against had sophisticated tactics, and in the end we lost a ragged game because we couldn’t find a way to make the most of it.

New Zealand, where even when in trouble, we try to solve the problem with the players as much as possible.

I feel that this style is in contrast to Japan, where the coaches give instructions when they are in trouble.

Switching (game speed) is slow.

Compared to Spanish and Japanese football, there is a considerable difference in the speed of changeover. It is very slow. In other words, the game develops more slowly, there is more space and it is more like a counter-attacking match.

As a midfield player, the pressure when you receive the ball in the pocket is very different. In Spain and Japan, you have to watch out for pressure from behind, but in New Zealand you don’t have to worry about that. You can have the ball with a lot of leeway.

I think the reason for this is because of the low fitness. It is not the fact that it is an amateur league that is the problem, but the fact that there is no professional league, which leads to a lack of motivation for the players. Therefore, there is no place to go up and therefore fitness is also low on average. A significant number of players are also overweight.

Low ambition.

My personal concern is the low ambition of young players.

In a country where there are no professional leagues, the option of earning a living from football is close to zero. The total number of children who say they want to be professional footballers is also quite low.

On top of that, the U20 rules mean that opportunities come around even if you don’t work hard. Perhaps there is also less motivation to work hard in order to compete.

I just want to get better. I just want to be better at football. There are very few players in New Zealand who have that kind of ambition. I think this is much less than in Australia.

Personally, I am concerned and feel very sad about it.

Strength on the ball.

I don’t know if you can call it a ball game, but the intensity of the collisions against the 50-50 ball is not half bad. The tackles are as big as you would expect from a rugby powerhouse.

I think Japanese people should be careful.

If you get hit by a ball, you will die.

What is ‘football in that country’?

Since I was a child, I liked to listen to stories from players who had experienced football abroad. I heard that Brazilian football is like this, Spanish football is like that, African football is brah brah brah. Whenever I heard such stories, I became interested in why football differs from country to country.

At the same time, I have always had the desire to actually experience it for myself.

I am a little bit proud of the fact that I have now played in several countries and felt the differences in each country.

I would have liked to have experienced football in more different countries, like Africa, Brazil or Argentina. But you have to remember that moving from one country to another is more demanding than fun.

I don’t have the mental strength to endure it at the moment, and above all, when I experienced Spain, which I had longed for, I had the feeling that the clouds that had been bothering me had cleared away.

So at the moment I have no intention of playing in a new country any more.

However, I still find it very interesting that ‘country and football’ and national identity are expressed in football. As a shallow learner, I still don’t know why this is, but I would like to keep thinking about it.

Next, I would like to write about the cultural football differences I felt in each country from an off-the-pitch perspective.

コメント