I recently attended a workshop called Positive Youth Development Aotearoa, Aotearoa is the Maori word for New Zealand and this workshop was, as the name suggests, about the development age in New Zealand football clubs. The workshop was, as the name suggests, about the development age of New Zealand’s football clubs. In a nutshell, the workshop was about communicating with players in the development age group.

Through this workshop, I discovered some of the problems that New Zealand’s development age group faces. At the same time, I also realised the structural and cultural differences between New Zealand and Japan in the developmental age groups. I would like to introduce some of the issues that I have identified through the workshop and communicate the cultural differences between Japan and New Zealand to both countries.

First of all, I would like to tell you that the problems I have experienced are only the problems I felt through the workshop. I have not coached in New Zealand yet, and I have only been coaching in Japan for a few years. The problems I see are only superficial, but even so, it was interesting to learn about the differences between Japan and New Zealand, so I would like to share them with you.

Problems faced by New Zealand’s developmental age groups.

Firstly, briefly, some of the issues in the developmental years in New Zealand that I felt through the workshop.

(i) Monster parents.

A topic that came up again and again throughout the workshop was dealing with parents who watch their children on the sidelines. It seems that parents in New Zealand, who are more aggressive than their Japanese counterparts, can sometimes become aggressive. Indeed, when I went to watch a game in the developmental age group, I was impressed by how aggressive the parents on the sidelines were in talking to their children. And we must not forget that this has become extreme at times, and that seemed to be one of the main problems.

(ii) The cost of children’s football activities, which is too high.

It is an earnest opinion that the cost of children playing football is too high. However, there is also an opinion that it is operationally impossible for the clubs to make it any cheaper, so we thought it was a fairly deep-rooted problem.

Other clubs’ intentions are that First Kicks (the first age group to start playing football (approx. 5-7 years old?)) The clubs also want to provide a free environment for First Kicks (the first age group to start playing football (approx. 5-7 years old?)) and are working to widen the window to football.

Some were also impressed to hear that they are working more carefully with girls’ football, which still has a small number of players, and are trying to create an environment that is free of charge and as pressure-free as possible.

(iii) The pick-up and drop-off issue

As will be explained in more detail later, in New Zealand, parents basically drive their children to and from school. This has caused a considerable burden on parents to pick up and drop off their children, and there are frequent problems with children not being able to participate in football due to their parents’ circumstances. This was exactly the same problem when I was coaching in Australia.

Comparison of developmental ages in New Zealand and Japan.

We will now compare the developmental age groups in New Zealand and Japan and introduce some cultural differences with respect to each country.

1) In Japan, the power of the coach is much stronger.

In my time playing football in Japan, I have rarely seen parents cheering on the sidelines as a problem (just my impression from growing up as a player). I am sure that Japanese people are shyer than their counterparts overseas, and I believe that the Japanese culture is one that respects the atmosphere and perspective of those around them. For better or worse, I believe this influences the behaviour of parents on the sidelines to “refrain from too much conspicuous behaviour”.

Also, in Japan, the leaders (coaches) have more power. I think there is a stronger atmosphere in Japan where the coaches are in charge of the team. Of course this is a good thing, but we must not forget that when this goes too far, it triggers problems such as excessive unreasonableness and power harassment. However, strict coaching, such as running punishments and sermonising, is still practised in Japan’s upbringing age group.

I think it is clear that the difference in the way coaches and parents are in Japan and New Zealand is due to the difference in education.

In Japan, there are still strong vestiges of military education. The educational philosophy that hard practice, training and mental hardship will make a person stronger is particularly strong in sports. As someone who has experienced a certain amount of unreasonableness, I can nod my head in agreement, but it is also something I do not want to nod. Unreasonable experiences may indeed make people stronger, but I have seen many people abroad who have not experienced such education fighting with great courage. When you think about it, it may just be our assumption that unreasonableness makes people stronger.

On the other hand, education in New Zealand does not allow for ‘scolding’ or ‘getting angry’. Violence, as well as shouting and one-sided anger, are educationally out of bounds. This makes it impossible to provide the kind of strict coaching seen in Japan’s upbringing years. Perhaps this makes it easier for parents to intrude into the coaching situation.

(ii) Both Japan and New Zealand have the same problem.

The problem of children’s football activity fees being too high. The same problem is occurring in Japan, New Zealand and maybe all over the world. Not only is there a participation fee to send a child to a club, but also equipment costs such as spikes and training clothes. My own life has strongly reminded me that football, which is supposed to be played with just one ball, actually costs a lot of money.

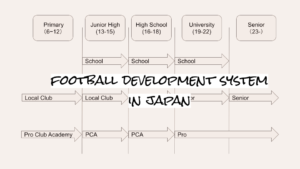

On a more structural note, in Japan, not only club-based football environments coexist, but also community-based football environments. In the primary schools age group, in addition to clubs (such as J-League and adult teams), there are also youth teams, which are mainly made up of children from the same area. These teams are mainly run by volunteers and the coaches are sometimes the children’s parents. Boys’ teams tend to be less expensive than clubs.

Similarly, clubs and club activities coexist in junior and senior high schools. Instead of running club and school club activities concurrently, as in New Zealand, players choose one environment or the other. In general, the club environment is more conducive, but it is not the case that club activities are inferior. In recent years, an increasing number of players have dared to choose club activities, which I believe is another unique Japanese culture.

The New Zealand football environment is club-based. The clubs that exist in a region consistently have players from the development age group to the senior team. One of the good things about this system is that because there are so many age groups in one club, there is also the opportunity for cross-generational involvement. Players who excel can easily be allowed to participate in training and matches in the older age groups. Another major advantage is that players can be developed over a long period of time, making it easier to establish an identity as a club.

It is quite interesting that New Zealand and Japan, which have such different structures, share the same problem of the difficulty of getting children to play football. Ideally, children should be able to play football for free (or at the lowest possible cost). On the other hand, it is also true that clubs need money to pay for coaches’ salaries, equipment and grounds.

Incidentally, the number of people coaching full time in New Zealand is not very high. The younger the age group, the more likely they are to volunteer as coaches.

In Japan, on the other hand, there are many people who coach full time, even in the primary school age group. I grew up in Japan and thought this was the norm, but it may be unusual worldwide. I have also heard that even in Spain, a major football country, most coaches have a separate full-time job and most of them have a coaching job that is almost part-time.

Perhaps this is due to the working pattern in Japan, where there is a lot of overtime work and it is difficult to juggle a full-time job and a coaching career. In New Zealand, where there is no overtime and work is flexible, it is easier to manage time and I think this makes it possible to have both a full-time job and a coaching job.

(iii) Pick-up and drop-off issues that may not be so familiar in Japan.

In Japan, compared to New Zealand, we don’t seem to hear much about the problems of transporting children to and from school (although of course there are probably endless problems). This is because Japan has good transport links, such as trains and buses. Above all, there is a culture of safety and security that makes it safe for children to go to school alone. In Japan, young schoolchildren can be seen riding the train to and from primary schools. In fact, this is the norm in Japan for Japanese people, but it is different overseas.

In New Zealand, it is rare to see primary school children on their own. The reason why ‘Hajimete no Otsukai (Old Enough)’ became a hit overseas was because it was strange for people overseas to see such a young child shopping alone. Even in New Zealand, it is against the law to leave children under 14 years of age alone. As such, it is inevitably the parents’ job to take their children to and from football. As mentioned above, it is important to remember that the ease of working in New Zealand makes it possible to pick up and drop off children.

Of course, this is influenced here not only by the security and culture, but also by the fact that New Zealand is a car-based society and the small number of clubs. Whatever the reason, I think it is a shame that children lose the opportunity to play football because of their parents’ circumstances (not being able to drop them off and pick them up).

Culture, education and.

It seems almost five years since I came abroad in 2019 (unbelievable). The first time I came to New Zealand, I discovered a lot of things that were different from Japan. And then I experienced Australia and Spain and came back to New Zealand again, and I still haven’t stopped discovering new things. The first time, I noticed more differences on the pitch than as a player. But now I find it interesting to discover differences from a macro perspective, from the club, the community and the environment. Most of these differences seem to be tied to culture and customs, not only in football, but also as a country or a people. The issues I felt during the PYDA and the differences I could see from Japan seem to be strongly influenced by education, land and population.

Unlike Japan, New Zealand has a small population and is a regional society. It is a multi-ethnic country and languages are spoken. Japan, on the other hand, speaks only Japanese. There must be many differences due to language as well. There are endless stories lying around and I am sure I will still be able to enjoy living abroad. I will do my best.

コメント